I’m getting close to giving up on metrics altogether.

It isn’t that metrics aren’t important. It’s that in so many cases they seem to do so much more harm than good.

Consider, for example, the lowly customer service call center—the place a company’s customers … its real paying customers … dial when something isn’t as they’d like it.

Lowly? Yes, lowly, because like it or not, few companies have much respect for their customer service call centers.

Want proof? Ask yourself this: What is a company’s best source of information about what characteristics of its products and services aren’t satisfying customers as they should?

The answer would be obvious even had I not just telegraphed the punch: The customer service call center.

Second question: How many companies analyze the calls to their customer service call centers to find out what customers are calling to complain about?

Answer: I have no idea, other than knowing that whenever I call one and ask if the person I’m speaking to has any feedback channel for passing along suggestions from customers. The unvarying answer is no.

Third question: What do companies measure about their call centers? Queue time. Abandon rates. Average call time. A few … and these count as advanced compared to most of what you’ll find out there … measure the first-contact problem resolution percentage and time to problem resolution.

Ever hear of a call center that’s measured on the number of product improvement suggestions it generates? How about one that’s measured on how many customer-eliminating business practices it identifies?

Me neither.

Look, companies pay good money to get their Net Promoter Score—a strategic metric that, instead of trying to measure the elusive “customer satisfaction,” measures how likely it is that a customer will recommend them to friends, colleagues, and other associates.

They’re paying to get the likelihood without gaining any insight into why that likelihood is as good or as bad as it is, when they could, instead, gain insight into why that likelihood isn’t better for a cost of … let’s see, divide by pi and multiply by the square root of a potato … for whatever it costs to ask call center employees what customers have told them.

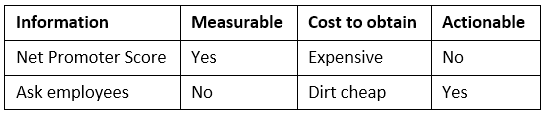

To summarize:

Peter Drucker famously said, if you can’t measure you can’t manage. Call it Drucker’s Metrics Dictum — DMD if you’re acronymically minded. At the risk of being criticized for criticizing the patron saint of management consulting (and please understand, I have immense respect for Dr. Drucker’s overall opus), the above table shows just how wrong DMD is. NPS is measurable. That’s its point. But it isn’t actionable.

And if a piece of information isn’t actionable, it doesn’t help you manage one bit.

Let’s start over, with a better understanding of what metrics are for. To get there, start with this: There are two kinds of metrics. One measures progress toward or achievement of goals, he other measures the current state and trend of controls, a control being a factor that contributes to making progress toward or achieving a goal.

Second: Goals and controls are fractal, which is to say, when you zoom in, every control becomes a goal with its own controls, and so on ad infinitum, ad nauseum, and ad only enough layers that you’ve reached the point of the obvious.

If, that is, you can map out a complete set of controls for a particular goal, and you can define useful and tallyable metrics for every control, then you really can measure things in a way that helps you manage them.

And: Metrics serve two purposes. One is to help management understand how it’s doing. The second is to drive employee behavior in the right direction, which explains Lewis’s Law of Metrics: You get what you measure—that’s the risk you take.

Set a goal and employees will help you achieve it. Establish a metric and employees will make that their goal — they’ll move the metric in the right direction, whether or not the steps they take to move it are actually good for the business.

Why would they do anything else?

Metrics tell managers how they’re doing and they tell employees what management wants. If metrics were completely out of the question, do you think you could find other ways to achieve these two goals?

I *really* gotta stop; probably a browser issue again:

> he other measures

*THE* other measures

Great stuff Bob. I’ve never cared much for relying solely on metrics for much of anything, and this explains it well..

Tweeted as @PerlDBA

Outstanding, really good stuff. But if you only get what you measure, doesn’t that imply that you have to first survey customers to find out why they are choosing your company? And then interview employees both individually and in groups to find out exactly what their procedures are that create the product that the customers are choosing to buy?

Once you actually understand the results of these first two efforts, then, it could be useful to use well-conceived metrics.

metrics are just the ‘how’, not the ‘why’.

A few years back we got into an even worse situation – middle management using the ‘stick’ approach to driving metrics in the direction their bosses wanted – only to find the metrically driven quitting and leaving the middle management in an utter mess. Their excuse “we had no alternative”. Which is a shame, and very disheartening for the rest of us.

As I pointed out to one manager who insisted that all calls can be completed in 2 hours – if we don’t know what the customer is calling about we can’t guarantee that. If on the other hand 2 hours was the point of ‘tell me about it, so that we can see if there’s anything we can do about it’ that would be the better solution. Their retort: “what, I have to do real work?”.

I have a crazy idea – maybe we should set the metric target of one group on the other. So customer service queue time – that’s the Engineering department’s problem. Development lead time – that’s up to customer services to solve. How would that hang?

Assuming that you still have measures, then smallish, focused businesses with good people at all levels could certainly manage without metrics – they could actually talk with each others, customers, competitors etc.

But as organizations get larger, with more areas of interest and greater levels of management and higher risk that they will have a normal bell curve of management competence, the more metrics are used as crutch.

Literally right after reading this piece, I got the following in LinkedIn i.e. another reason metrics won’t go away, is too many job depend on it. (And don’t you love it when you can get the ‘complete guide’ for free!)

Free E-Book – How to Create Compelling Business Dashboards – Complete Guide

Everything you need to know to design best-practice dashboards and data visualisations.

Bob is right-on concerning goals vs metrics. A real-world example that everyone can wrap their head around is the Veteran’s Administration scandal. Set a metric and come come hell or high water, employees (and management) will find a way to meet it…even if it is to the detriment of their customers and the organization.

A goal challenges behavior…a metric excuses it.

In a previous life, I was in responsible for all systems and storage for a somewhat large data center service ~35K employees. And while not directly responsible for the Call Center, I say near the folks who worked in that area.

An issue came up wherein the queue depth was 15-20 calls all day long. Resolution times tended to be in the 15-20 minute range with some approaching an hour. So the Call Center manager setup a meeting with his peers and his manager. He also made a mistake in inviting me to the meeting. You’ll understand the “mistake” part here in a moment.

Prior to the meeting, I went and talked with a number of the folks in the Call Center. I verified that the issue was real (it was). So I asked what was it that they spent their time on, looking to see if I could find a pattern. Turns out, it was easy to find.

They told me there was one application that was causing our users grief. And it was just one commonly used portion of the app that was both confusing and error prone. So I reasoned that if we could fix this part of the app, we could provide a good deal of relief.

Being an engineer at heart (i.e., I like to create a fix things), I called up the project lead for the app, explained the situation, the problems we were having, and asked if he could fix the issues. Unaware of the problem, he thought about it for a moment and said, “Sure, we can have this fixed up a week or so. We’ll add it to the next release coming up here shortly.” Good: that was a perfect answer.

So the day of the big meeting arrived. I listed as the Call Center manager provided all kinds of metrics showing that his team was overwhelmed. From those metrics, his solution was to add another 10 FTEs to his team. That should bring the metrics back down to acceptable level. Running all the systems and aware of performance metrics, they asked me what I thought. This was their fatal mistake.

So I related the research I had done. I let them know that the app’s project leader said he would have the cause of the problem fixed and an updated release out in a week or two. The room because eerily silent. I was asked to leave which I did but, being young and blissfully ignorant of things management, I had no clue as to what had just happened.

Later I came to find out that the Call Center manager did not want a solution to the problem; he wanted to expand his fiefdom. By increasing his headcount, he would move up a notch in the management scheme of things and thus get more pay. But with me providing a solution rather than a Band-aid, I kind of put the kibosh on his expansion plans. He wanted to grow his kingdom; I wanted to solve the problem: opposite ends to the same issue.

Moral: you need some metrics to help keep you aware and help you decide, but more than that, you need to apply some common sense in their use and interpretation for any given situation.

Well said Bob. One thing I would add that would make for another great column (hint, hint). The danger of dare I day Big Data and metrics. I am amazed how often I see people look to prove their metric and guess what — they usually do! In business, we compensate people to hit metrics and they usually figure out a way to do it, ignoring what the data is really telling them or at the cost of something else that is much more important. You know all of that, heck I think you taught me most of it. But a refresher never hurts.

I have often thought we rely too much on numbers. A problem I often see is that people who know little or nothing about statistics put together cherry picked numbers to support a hypothesis. On a Powerpoint chart these numbers look impressive but really have no significance. Ditto for surveys, anyone can create a survey these days but because they don’t understand how to create a good survey the results are not a good basis for strategic decisions.

I work in tiny dev shop for a small government agency and we have an application with 2000 users, 25 power users who are the main callers. Our parent agency keeps wanting to push call tracking software for our helpdesk and we keep having to fight it.

They told us we’d know how many calls we get. We told them our customers don’t care.

We had a meeting and they talked about measuring call time and I told them if they actually cared about the entire _process_ instead of just the help desk, they’d expect that over time with the same application and the same set of users that the calls should get rarer and rarer and become longer and longer and more difficult to fix because you should fix everything that causes calls.

You don’t count the number of calls and act like that’s the most important outcome.

If you listen to the teachers in the U.S. you will hear very similar thoughts regarding congressionally imposed metrics on the profession of teaching. They often make comments about spending so much time making sure that they improve their metric that they don’t actually teach anything that isn’t on their metric (i.e. the test that the kids are congressionally mandated to take.)

Add to that my pet peeve about No Child Left Behind: No Teachers Were Involved in devising the law.

For a long time I have said that support to outside (real) customers should be run by the marketing department. Their entire existence is based on future return on investment.

Maybe bring in some marketing types if you are going to use metrics for your call center?

Back when I did more CRM consulting I often suggested having the customer service call center report to the head of marketing, for the same reasons you cited.

This article prompts an update on an old quote: There are lies, damned lies, and metrics.

Metrics were created to fill a purpose, and when used correctly can be useful: to demonstrate that things aren’t actually the way people think they are; to keep upper management informed in an organization that’s too big for conversations to work accurately.

That last point may apply to smaller orgs too – all you need is one middle manager to tell the boss what he thinks the boss wants to hear instead of what’s actually occurring and your “talk to people” solution falls apart. Which is why metrics were created. Presumably they were harder to fake than pure words in a report.

Which brings us back to the modified quote. Metrics can be useful, but like statistics, you have to know exactly what you are doing with them.

I’d be all for a replacement, but I don’t know what that would be. I think the first thing to be defined in looking for a replacement is what actual problem metrics were created to fix. Most likely they’re being used to address a bunch of disparate issues; each issue may be better suited to a different solution.

Also speaking of customer service issues I’ve noticed that the “permalink” on the email newsletter seems to go to the previous week’s article instead of the one in the email.

It’s a manual process, which means occasionally I miss a step. Sorry for the inconvenience.

As usual: You did nail it!

Answer 1: Drama would have been if told several stories like Mr. Drabicky’s, yours are notes to “keep the joint running”.

Answer 2: Metrics are just quantitative linkages to something else; my take on metrics is to use them to keep context of “relevant somethings” like customers, team performance, earnings, expenses, economic situation, etc. In this line, substitution of any metric is just a change of references and/or correlations, the real task is to “have a meaningful perspective”.

¡Un abrazo!

Bob,

In reference to your NCLB pet peeve, how many laws are formulated with involvement from subject matter experts generally? I have often wondered how people who don’t know anything about a particular subject can make laws about them.

As it happens, that’s the claim lobbyists generally make – that they aren’t just representing pressure groups. They’re helping law makers craft better laws because they and the groups they represent have a lot of knowledge about the subject.

I’ll leave it to you to decide how well that’s working out.