Which matters more, working on what’s most important, or doing whatever you’re working on well?

I raised the question a couple of weeks ago and several correspondents asked for more. Here goes.

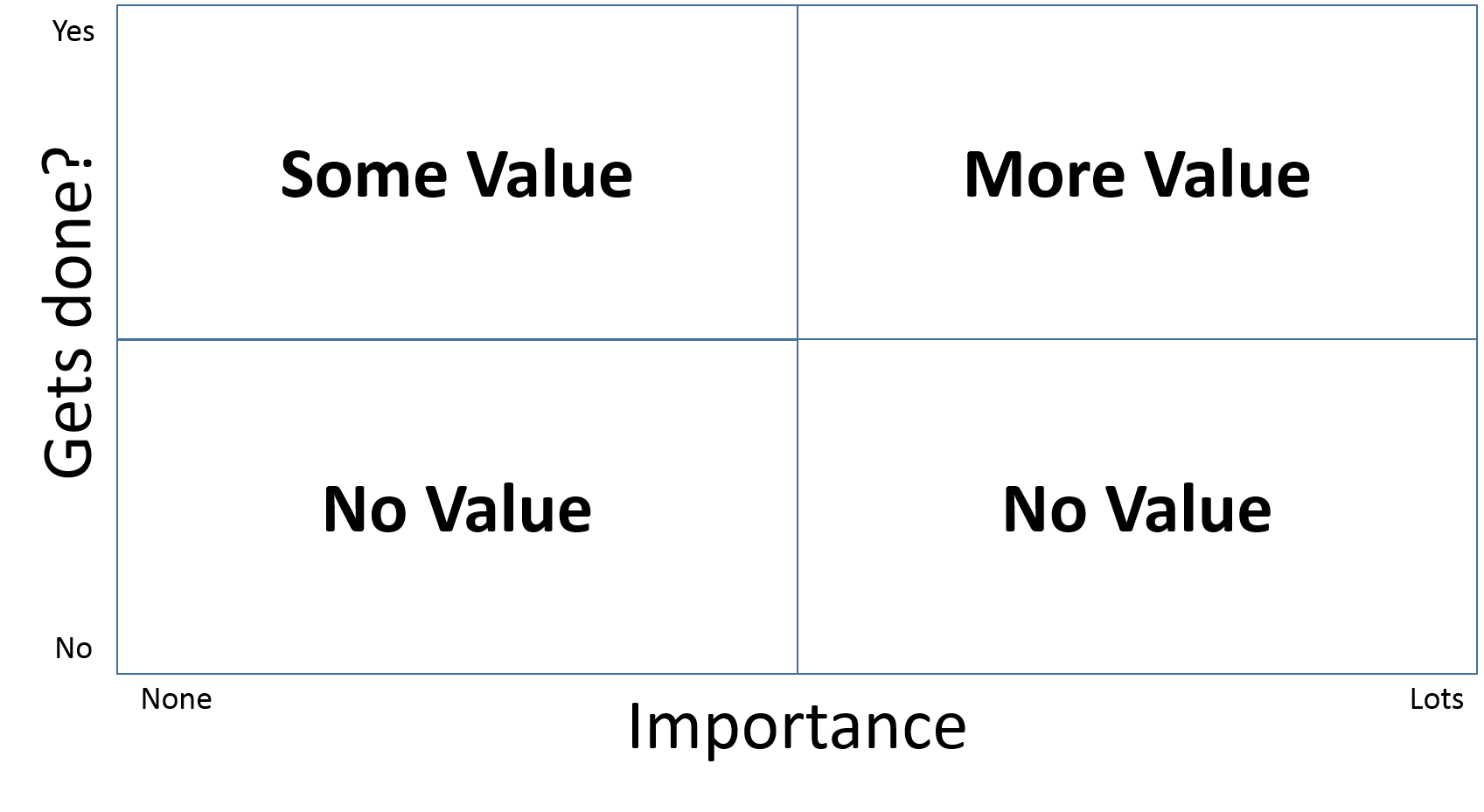

As the figure shows, doing the work matters more, because no matter what you’re working on, if you never get it done, or deliver junk when it does get done, you won’t deliver any value (no, this isn’t intended to be “ripped from today’s headlines.”)

So unless you or whoever gives you your assignments has truly horrible judgment, if you get the job done, whatever the job, you will deliver some value.

Which means that if both IT governance … budgeting and priority-setting … and delivery are broken, fix delivery, because in the greater scheme of things, doing the work is always more important than managing the work.

More important, at least, if your measure is the value you deliver. If you value ego-gratification or the amount of power and influence you have, that’s a different matter.

But not entirely, because if those who set direction and manage the work don’t run competent organizations, they’ll need to add blame-shifting to their repertoire of management skills. Otherwise, the visibility they crave will backfire.

Which is the logic behind guideline #7 of the KJR Manifesto — before you can be strategic you have to be competent. If you can’t deliver the goods, nobody will care about your brilliant insights.

Especially with respect to IT, there’s another reason competence trumps priority-setting in the corporate hierarchy of values, and it’s a nice irony: If priority-setting is more important than getting the work done, that just elevates the importance of getting the work done even more, because there are only two meaningful outcomes of the IT priority-setting process — scheduling or rejection.

It’s like this: A list of projects, ranked by priority, is more or less useless. Some projects need the deliverables of other projects, so they can’t start until their predecessors are done no matter what their priority. Others depend on staff assigned to other projects too, so one or the other has to wait.

And, business planners, being planners, have an annoying habit of wanting to know what’s going to get done this year.

Right down at its core, what IT governance does, then, (really, business change governance but that’s a well-worn topic here so let’s not quibble) is maintain a projects master schedule. And because what determines when one project on the master schedule can start is when projects it depends on actually finish, they’d better finish on time. Predictably on time.

It’s that competence thing — without it, the project master schedule is just pretending.

Doing the work is always more important than managing the work. Want more evidence? Let’s go to annoying sports metaphors. Like, in football, the basic blocking and tackling wins more games than calling brilliant plays.

If you prefer baseball, if you don’t have great bunters and fast runners, there’s no point calling a suicide squeeze.

Perhaps you like historical metaphors. Consider the case of George Washington. By any reasonable measure he was barely competent at strategy and tactics, and any ability he might have had at logistics was subverted by the Continental Congress. What made Washington a great general was his ability to turn his troops into a professional army, and his ability to keep his army together (I’m relying mostly on David McCullough’s 1776 for this interpretation).

Does this mean leaders and managers are unimportant? Of course not. Executives and managers who have outstanding talent in their organizations and who manage high-performing teams are in that position because they’ve developed the ability to attract, recruit, retain, develop and promote the best employees in their fields.

Oh, and there’s one more reason doing the work is more important than managing the work.

Imagine you’re a manager. The employees who report to you aren’t particularly good at what they do, and they don’t function well as a team either. But, you figure you’re a good enough manager to overcome this disadvantage. So you start to hold people accountable, hold their feet to the fire, and hold their hands when they need it.

All this holding takes a lot of time and attention. Where does it come from? From your ability to gather information and think about what it means … exactly what you can’t afford if you think what matters is setting brilliant strategies and tactics, and making smart decisions.

It’s the Edison Ratio one more time: Genius isn’t just one percent inspiration and ninety-nine percent perspiration. If the 99% isn’t very good, there won’t be any time left for the 1%.

Wow Bob – “…this isn’t intended to be “ripped from today’s headlines.””?!? Methinks the lady doth protest too much… Directly to your point – this administration clearly lacks competence – primarily due to lack any prior executive experience. As one wag commented ‘the goverement sucks at project management’ – not to mention actual execution. Take the partisan blinders off – you missed an opportunity to critique an important topic.

Seriously? Partisan blinders? So now, bad project execution is a partisan topic too?

By the way, if the government sucks at project management, please explain the three Mars rover missions to me.

In any event, I’m planning to cover this topic next week.

Too long ago to remember the citation (AMA maybe?), a course instructor offered a very telling cost/benefit metric for this topic, which I will paraphrase in terms from your column:

A competent team of N players will usually accomplish something of value. Adding a manager should mean that the team becomes more productive than they would have been as N+1 players (adding a doer instead, and ignoring the pay biases that managers typically grant themselves). Any manager whose contribution doesn’t yield at least that much improvement doesn’t measure up.

(I was a manager once, but opted back to being a doer because of the associated stresses that you elaborate so well in every KJR.)