Why would a CEO hire a CIO, anyway?

My friend and colleague Mike Benz – a talented CIO himself – answered this question in a recent LinkedIn post, providing ten reasons it’s a good idea.

But with all due deference to someone who knows the subject well … and someone I hope is still my friend after reading what follows … I think Mike’s asking the wrong question.

From the perspective of most CEOs, “CIO” and “the poor, sorry zhlub I hired to run IT” are synonyms, so their answer to “Why hire a chief information officer?” is, “Well, someone has to run IT, and I sure don’t want to do it.”

Which leads to this week’s question: What, if anything, is the difference between “CIO” and “Poor, sorry zhlub”?

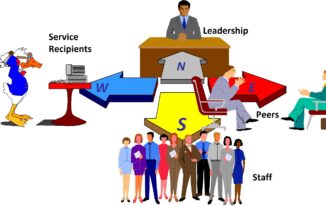

You can find one answer in the Management Compass, which I introduced way back in 1997. As you can see from the diagram, CIOs lead and manage in four directions: North, to the company’s top executives, east, to their peers in other parts of the business, west, to those who make use of IT’s services (no, not “internal customers”!), and south, to IT’s employees.

As a general rule, poor, sorry zhlubs focus most of their leadership time and energy on IT’s employees and making sure IT takes care of its service recipients … southwest on the compass, that is.

They focus on delivery.

CIOs, as an equally general rule, face nor’east more often than not. In doing so they can, if they aren’t careful, put their southwesterly priorities at risk through inattention.

Poor, sorry zhlubs, also known as IT directors, do their best to make sure IT gets the job done. But it can be the CIOs, who pay more attention to their peer and executive relationships, who get IT the respect and resources it needs to get the job done.

And while they’re at it the CIOs in this admittedly simplistic portrayal enjoy more career success than their southwest-oriented brethren – something you’d expect for folks who cultivate their skills at managing up.

The obvious resolution to the dueling IT leads conundrum is for whoever sits in the head-of-IT chair to consciously and deliberately pay attention to all four compass points.

In addition to being obvious, this solution has the added benefit of being right.

But there’s a catch (isn’t there always?). The catch is the head of IT’s comfort zone. “Yes,” you can imagine a southwesterly IT director saying. “I know I should be building and maintaining all of these relationships. But the executive leadership team alone has a half-dozen members, and they’re all busy without giving me time for relationship-building. And my calendar is already full before I try to schedule these meetings.”

Which is to say that with all due respect to Star Trek, space isn’t the final frontier. That honor belongs to time.

Bob’s last word: And one more thing. In theory, or at least in a lot of what you’re likely to read about such things, CIOs, in contrast to their IT director brethren, are strategic thinkers and bring their strategic thinking to the executive suite.

Me too. There’s No Such Thing as an IT Project includes clear guidance that IT ought to be leading company strategy.

But then there’s the guidance provided in an earlier book, Keep the Joint Running. It points out that before IT gets to be strategic, it first has to be competent.

CIOs, that is, might be better at sitting at the strategy table, but wearing their IT director hat might be what gets them there.

Now playing on CIO.com’s CIO Survival Guide: “4 hard truths of multivendor outsourcing.”