Imagine your company, like so many others, makes use of some form of stacked ranking system in its employee performance management process.

Now imagine you’re the CIO, and don’t much like it.

What do you do about it?

Business executives find themselves in this sort of situation all the time. It’s why politics is a good thing, in spite of the word’s negative connotations: Politics is the art of finding a way forward when people disagree about the best path forward.

Which is pretty much every time people (1) have to find a path forward; and (2) aren’t alone.

Another piece of the puzzle: There’s an immeasurable but critical aspect to personal effectiveness when you’re an executive, called political capital. Perhaps you’ve heard of it. If you haven’t, you probably haven’t accumulated any. If you have, you know … it’s a combination of trust earned, favors provided, and reputation acquired for not needlessly making waves over every decision you don’t completely agree with.

If you’ve accumulated political capital, live with stacked ranking, and don’t like it, you probably … and probably, wisely … decided there’s no point expending any trying to fight it.

When you’re an executive, that is, you often have to support positions you don’t entirely agree with, and sometimes have to support positions you vehemently disagree with.

Support? Yes, support. From a personal-integrity perspective, this can be something of a challenge, as when someone who reports to you asks you point blank how you can defend such a cockamamie system. Your alternatives:

- “Yes, it is a cockamamie system, but you know what those bureaucrats in HR are like.”

- “As leaders we need to take responsibility for recognizing that some employees aren’t measuring up. This is part of it.”

- “Gee, I’m late for a meeting. We’ll have to continue this conversation another time.”

Better but not good: “I don’t fully agree with a lot of things. When I don’t I’m not always right. Regardless, when the organization makes decisions I support them because that’s part of being a leader. And no, I won’t list which ones I do and don’t like.”

However you decide to answer, stacked ranking really fits only a very particular circumstance — an organization plagued with complacency and mediocrity, and overstaffed because of it. Any place else it’s a seriously bad idea.

So let’s pretend, just among ourselves, you think getting rid of stacked ranking is important enough that you’re willing to do something about it. Your first step is to find out why the company first adopted the practice. Make sure the original root cause has been fixed. Otherwise, don’t even try.

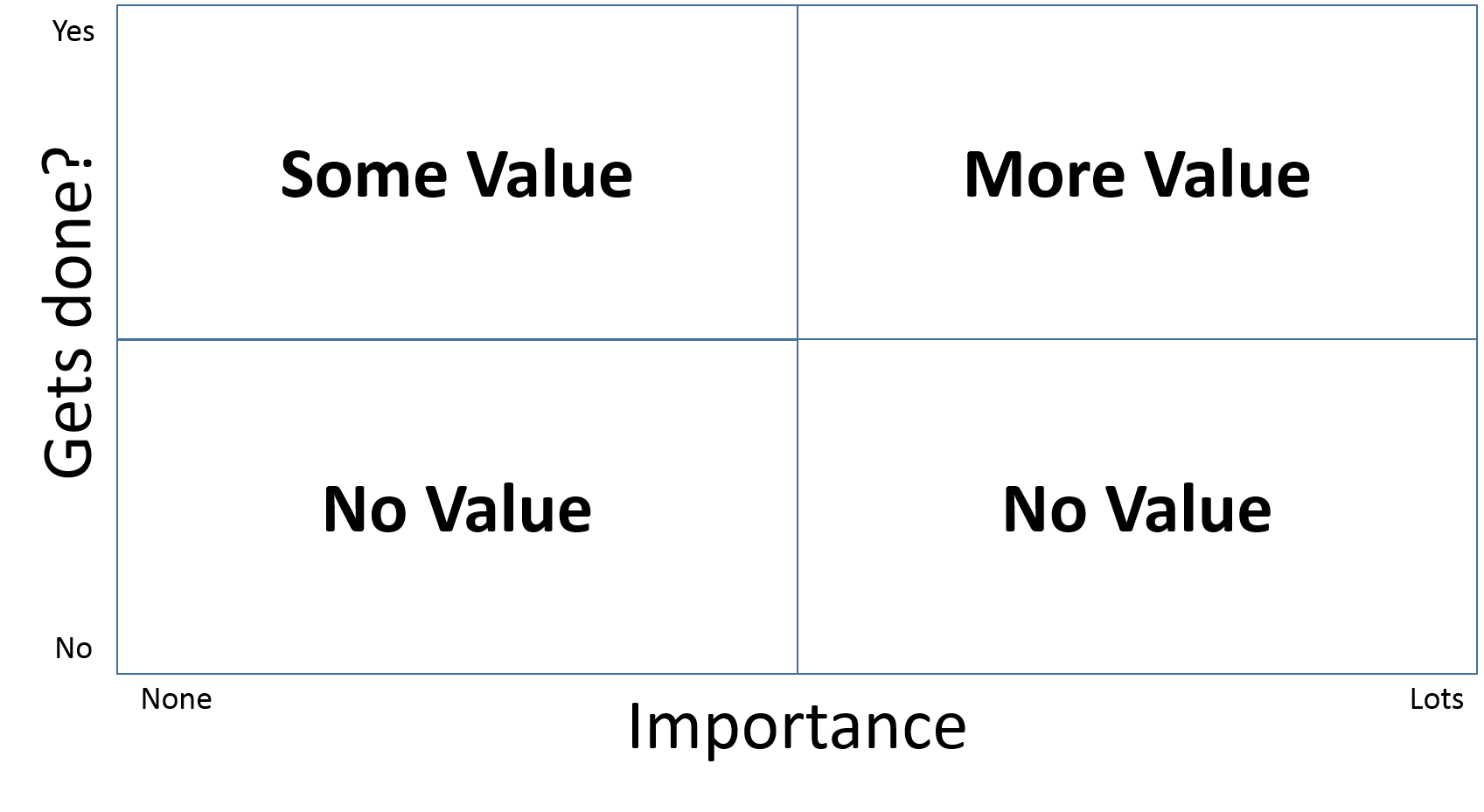

If you’re still willing to expend some of that political capital we were talking about earlier, as with financial capital, a willingness to spend the political kind isn’t the same as the knowing what to spend it on.

Your down payment is discreetly discussing the matter with your closest confidants among your fellow executives. If you’re all alone in this, give up, and unless they think there’s likely to be significant support for the change among the rest of the executive leadership team, give up.

Next: Amass literature that supports your position, and that offers practical alternatives, because whatever its flaws, stacked ranking is practical. Also, with your confidants, accumulate a half-dozen to a dozen examples of good employees who left the company because of the system.

Next: Assess the head of Human Resources. He or she might be wanting to change the system, but not brave (or foolish) enough to take the lead. If so, make HR your next stop. If not, wait until just after the next review cycle — changing a system like this mid-cycle is worse than having the system. Timing matters.

Then, meet with the CEO. Announce the subject. Provide the best of the best of the literature. Explain that you’ve spoken with quite a few members of the executive team, and there’s a lot of support for doing something different.

Ask to put the subject on the agenda of the next executive leadership team meeting, at which you make your points and suggest the company bring in some independent experts to assess the situation and recommend a course of action.

Yes, consultants. There is a place in the world for them (us), and this is one of them … defusing a politically explosive situation by providing an independent perspective.

Because part of winning the point is acknowledging you might be wrong about it.

One more thing: Win or lose, your political capital is now depleted. Don’t take any other strong stands until you’ve had a chance to replenish it.

* * *

Don’t worry. I’m not trying to drum up business. This isn’t one of my consulting topics. It isn’t even one of our (aka Dell Global Business Consulting’s) topics.