Humans are the collaborating animal.

Sure, bees dance, termites build mounds, and wolves and orcas hunt in packs. But no other animal gets together to build anything on the level of skyscrapers or Mars rovers, to fight in anything resembling a human armed force, or compose and then sing barbershop quartets, let alone symphonies.

But for every successful collaboration there are probably ten that fail, whether they’re ERP implementations, failed designs for a 9/11 memorial, most legislation, or every Pirates of the Caribbean sequel and every other Disney-theme-park-ride-turned-into-a-movie.

What goes wrong? With Disney, it’s probably the need to manufacture another movie even if nobody has had even a tiny spark of inspiration to justify one. For the rest …

Often, the problem comes down to different people from different organizations coming to the party with different hidden assumptions. When these go undetected and unresolved, the usual outcome is something less than success.

Two weeks ago we looked at one aspect of the situation: How each party values the three bottom-line goods of business — revenue, cost, and risk.

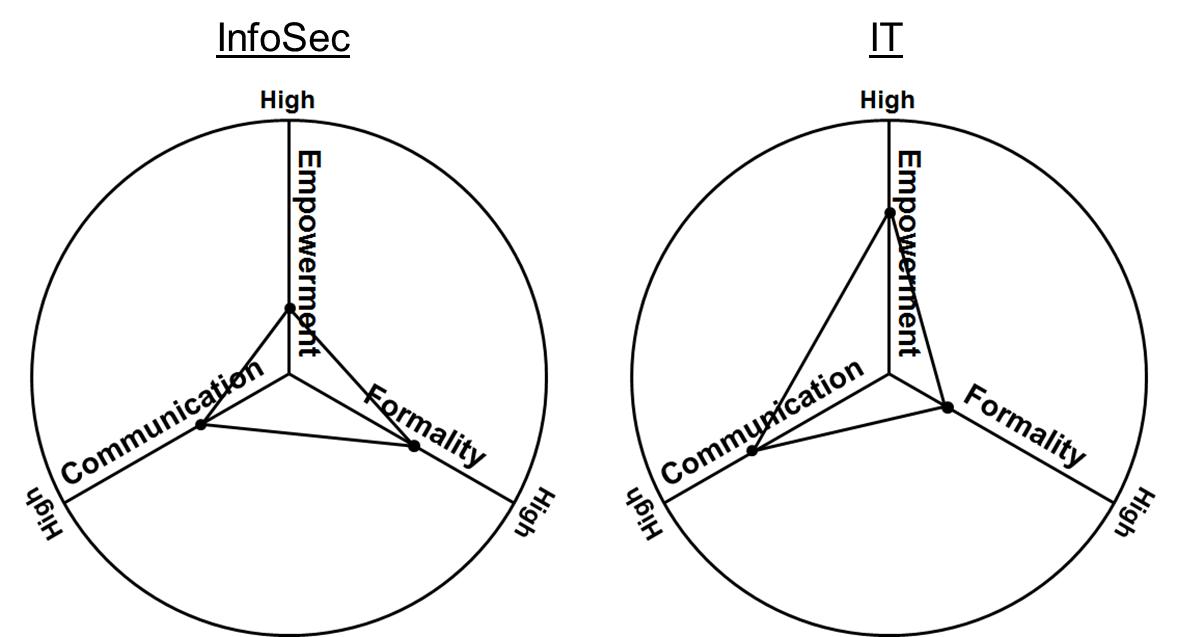

Last week we looked at a second aspect of it: How organizational styles compare, and in particular their levels of empowerment, formality, and communication.

This week we look at one more aspect: Each organization’s operating mode.

At the risk of oversimplifying, organizations have three ways to do their work.

The first is to work through processes and procedures, which is to say recipes. Everything is specified, and if everyone just follows the steps as they’re described, the result will be what it’s supposed to be.

The second is to work in accordance with “practices.” Like processes, practices are organized into an accepted series of steps to follow. Unlike processes, in a practice the specifics are left to the practitioners, who are expected to apply their knowledge, experience, and judgment to each situation they face.

The third is to innovate and improvise — to figure things out based on the logic and context of each situation.

The way it ought to be is that for each type of work that has to get done, the organization responsible for it makes a conscious choice from among these three ways of working, recognizing that really, they aren’t categories so much as they’re three poles in a continuum of possibilities.

The way it usually does work is that for each type of work, whoever does it chooses whichever approach they like the best — the decisions come from hidden assumptions, not explicit analysis.

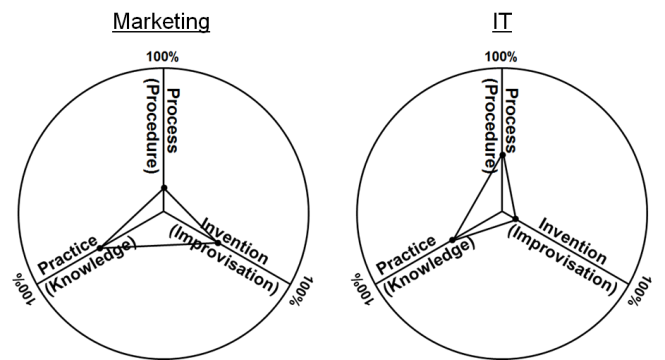

Likewise IT. So when the two organizations try to collaborate, their two sets of preferences don’t line up, because why would they?

Imagine, just for the sake of argument, that IT’s overall operating mode strikes an even balance between process and practice, with very little improvisation going on.

Now imagine the other organization IT has to collaborate with is Marketing. As the figure illustrates, our mythical Marketing organization is heavy on practice and improvisation. Following recipes just isn’t in its DNA.

Now what?

The starting point is to be conscious: of your own organization’s preferences, and those of the organization you’ll be collaborating with. How can you find out?

Ask. Not using this vocabulary, which might seem strange to anyone who doesn’t read Keep the Joint Running. But just asking, as in, “Tell me about the kinds of work you do here.”

As you listen, keep an ear out for key phrases like, “We just do what makes sense,” a tip-off that improvisation is important there. Or, “This is how we do things around here,” which sounds a lot like process.

“We know our business and get the job done”? That’s a practice orientation.

It will take some conversation, some reading between the lines, and eventually, perhaps, after you’ve built some rapport, some time spent familiarizing your colleagues in Marketing (or wherever) with these concepts. At some point in the conversation you’ll familiarize your colleagues with your IT self-assessment, and you can ask for their self-assessment.

Better yet, you’ll be able to discuss why IT is what it is and why Marketing is what it is.

That’s when both organizations will stop choosing their operating mode based on personal preference and start deciding based on the logic of their (and your) circumstances.

Once you’ve achieved that, you’ll be in a very good position to help your colleagues solve the problems they have in ways that will fit their operating mode, rather than trying to force-fit them into yours.

That’s preferable for a very simple reason: If your solutions fit their operating mode, they might actually adopt them.