IT management and business leadership often think differently about investing in the business. How about you?

Here’s an exercise worth doing for any IT leader:

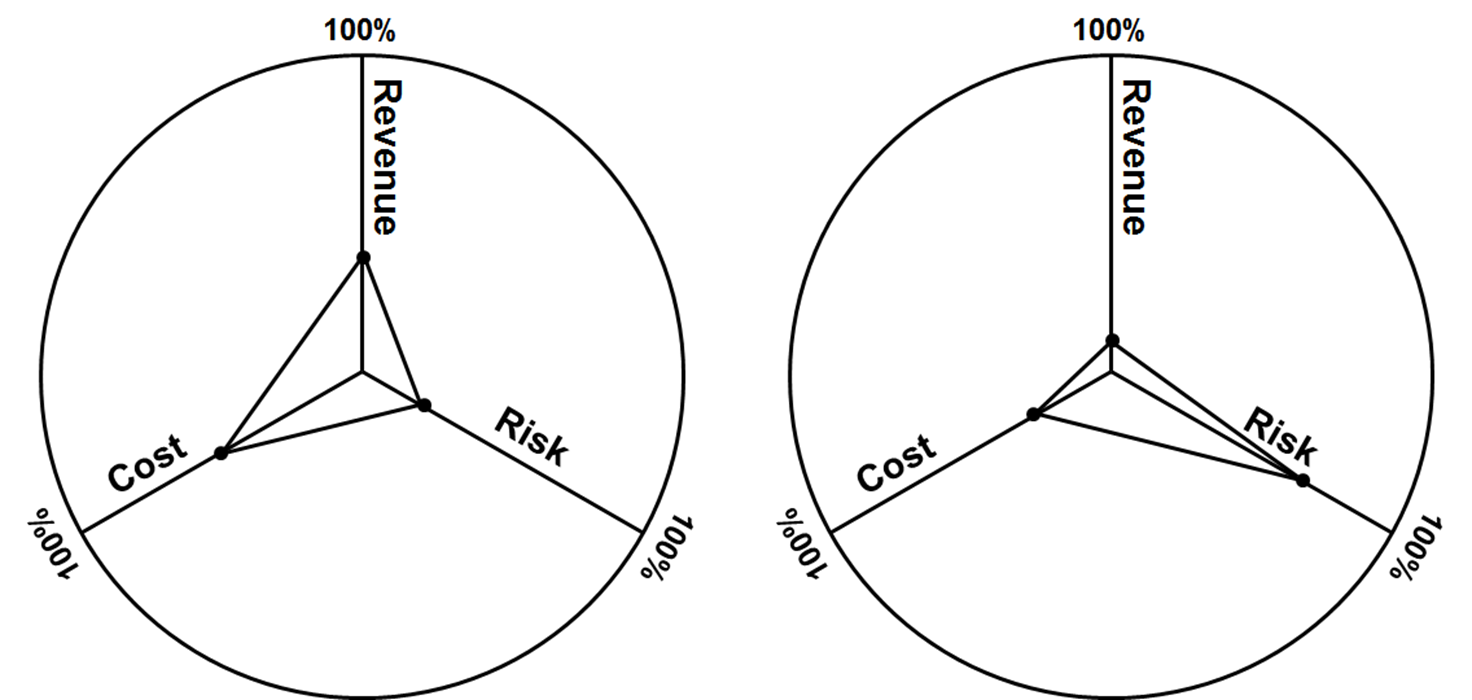

Canvas your company’s top executives. The question: They have $1 million to allocate. They can invest it in revenue enhancement, cost reduction, or risk management — the three bottom-line metrics for any for-profit business. How much do they put in each category.

If you have an IT Steering Committee and its members aren’t the company’s top executives, ask its members, too.

Finally, ask your IT leadership team members the same question: If they were running the company, how would they invest?

Average the results for each group and graph them. They’ll probably look something like the figure.

What’s going on? In my experience, business executives tend to focus more of their attention on cost-reduction than anything else. That’s because it’s generally possible connect the results of a project that’s supposed to reduce costs to actual cost reductions.

Projects that are supposed to increase revenue? Unless it’s a direct marketing campaign, a website change tested through the use of software that presents the old view to one set of visitors and the new view to a different set, or a new product, it’s embarrassingly difficult to prove that any particular action a company takes results in more revenue.

Strange to say, investments in revenue are riskier than investments in cost reduction.

Entrepreneurs are different: They tend to emphasize revenue enhancement more than cost reduction.

And risk management? For both entrepreneurs and business executives, investments in risk management are beyond risky. Here’s why:

There are three ways to invest in risk management: Prevention (aka Avoidance), which reduces the odds of a bad thing happening; mitigation, which reduces the damage done by a bad thing that happens; and insurance, which spreads the cost if a bad thing happens.

If a bad thing doesn’t happen, there’s no way to know if it didn’t happen because of the company’s prevention efforts, because there was no risk in the first place, or the company was just lucky.

If a bad thing does happen, there’s no way to tell whether, without its risk mitigation efforts, the cost would have been higher or not.

It is true that if a bad thing happens then at least the company knows whether it insured for the right amount. But if a bad thing doesn’t happen then the money paid for insurance that year was wasted. Maybe the risk isn’t high enough to warrant the cost of the insurance.

Or maybe the company was just lucky this year. There’s no way to tell.

IT’s investment profile tends to be quite different. IT tends to get beat up all the time about What Technology Costs. More, since businesses first started to invest in computers the rationale has mostly been increased productivity — information technology is supposed to reduce costs. It’s no wonder IT management tends to focus heavily on cost reduction.

But even though we get beat up about What Technology Costs, that doesn’t hold a candle to the extent we’re beat up about when something bad happens to our technology. Whether our systems are hacked, a virus invades, or the systems are down for some other reason, we get beat up. And even if we don’t, we expect to get beaten up.

So IT management’s instinct is to invest in risk management more than in anything else.

That, coupled with what’s invested in cost reduction, doesn’t leave very much to help increase revenue.

Go through the exercise — make the numbers real. If your company’s business executives and IT management line up well, good for you. You’ve achieved “IT/business alignment” and are ready to take the next step: Business/IT integration, if you haven’t already.

If not, it would appear you have work to do.

One place to start: During each business planning cycle, suggest the strategic plan include investment targets for each of the three categories of investment: Revenue, cost, and risk.

You might even guide everyone involved through the exercise of listing the major ways to invest in each of them to get to a finer-grained level of investment planning.

However you approach this, your goal is to get everyone thinking about this subject the same way.

Because if you don’t succeed at this, it doesn’t matter what anyone said. The moment something bad happens … the moment a risk turns into a reality … all bets are off.

That’s when the blamestorming starts.