I’m getting close to giving up on metrics altogether.

It isn’t that metrics aren’t important. It’s that in so many cases they seem to do so much more harm than good.

Consider, for example, the lowly customer service call center—the place a company’s customers … its real paying customers … dial when something isn’t as they’d like it.

Lowly? Yes, lowly, because like it or not, few companies have much respect for their customer service call centers.

Want proof? Ask yourself this: What is a company’s best source of information about what characteristics of its products and services aren’t satisfying customers as they should?

The answer would be obvious even had I not just telegraphed the punch: The customer service call center.

Second question: How many companies analyze the calls to their customer service call centers to find out what customers are calling to complain about?

Answer: I have no idea, other than knowing that whenever I call one and ask if the person I’m speaking to has any feedback channel for passing along suggestions from customers. The unvarying answer is no.

Third question: What do companies measure about their call centers? Queue time. Abandon rates. Average call time. A few … and these count as advanced compared to most of what you’ll find out there … measure the first-contact problem resolution percentage and time to problem resolution.

Ever hear of a call center that’s measured on the number of product improvement suggestions it generates? How about one that’s measured on how many customer-eliminating business practices it identifies?

Me neither.

Look, companies pay good money to get their Net Promoter Score—a strategic metric that, instead of trying to measure the elusive “customer satisfaction,” measures how likely it is that a customer will recommend them to friends, colleagues, and other associates.

They’re paying to get the likelihood without gaining any insight into why that likelihood is as good or as bad as it is, when they could, instead, gain insight into why that likelihood isn’t better for a cost of … let’s see, divide by pi and multiply by the square root of a potato … for whatever it costs to ask call center employees what customers have told them.

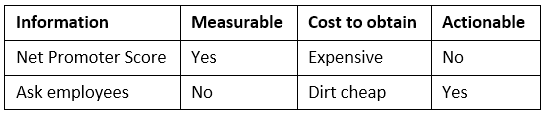

To summarize:

Peter Drucker famously said, if you can’t measure you can’t manage. Call it Drucker’s Metrics Dictum — DMD if you’re acronymically minded. At the risk of being criticized for criticizing the patron saint of management consulting (and please understand, I have immense respect for Dr. Drucker’s overall opus), the above table shows just how wrong DMD is. NPS is measurable. That’s its point. But it isn’t actionable.

And if a piece of information isn’t actionable, it doesn’t help you manage one bit.

Let’s start over, with a better understanding of what metrics are for. To get there, start with this: There are two kinds of metrics. One measures progress toward or achievement of goals, he other measures the current state and trend of controls, a control being a factor that contributes to making progress toward or achieving a goal.

Second: Goals and controls are fractal, which is to say, when you zoom in, every control becomes a goal with its own controls, and so on ad infinitum, ad nauseum, and ad only enough layers that you’ve reached the point of the obvious.

If, that is, you can map out a complete set of controls for a particular goal, and you can define useful and tallyable metrics for every control, then you really can measure things in a way that helps you manage them.

And: Metrics serve two purposes. One is to help management understand how it’s doing. The second is to drive employee behavior in the right direction, which explains Lewis’s Law of Metrics: You get what you measure—that’s the risk you take.

Set a goal and employees will help you achieve it. Establish a metric and employees will make that their goal — they’ll move the metric in the right direction, whether or not the steps they take to move it are actually good for the business.

Why would they do anything else?

Metrics tell managers how they’re doing and they tell employees what management wants. If metrics were completely out of the question, do you think you could find other ways to achieve these two goals?