“Why can’t we all just get along?” is the battle cry of the hopelessly naïve. There are plenty of reasons, ranging from:

- Different values (not better or worse values, just different ones).

- Disagreements about subjects we think are vital.

- We just have different styles, which aren’t entirely compatible with each other.

People who have to work together work together better if they get along with each other. The same is true of the departments within a business. To the extent they have different styles, getting along is harder. This, in fact, is an important reason companies put diversity programs into place … to help everyone understand that different styles aren’t better or worse styles.

They’re just different. The starting point for working together is to understand what those differences are.

Start with this: In a business of any size, there probably isn’t a “corporate style” that accurately describes every part of the organization. Like it or not, HR will have a different style than Accounting, which will have a different style than Sales and Marketing (we hope!), which will have a different style from manufacturing.

If the business is organized geographically, the Asian subsidiary will have a different style from the European subsidiary, which will have a different style from …

So from the perspective of IT’s need to manage relationships effectively, understanding the style of each group IT works with … and IT’s style, characterized in the same terms … matters a lot.

There’s no shortage of ways to characterize “style,” the most popular being to start with a blank sheet of paper and then to write whatever occurs to you. If you’d like something more structured try this:

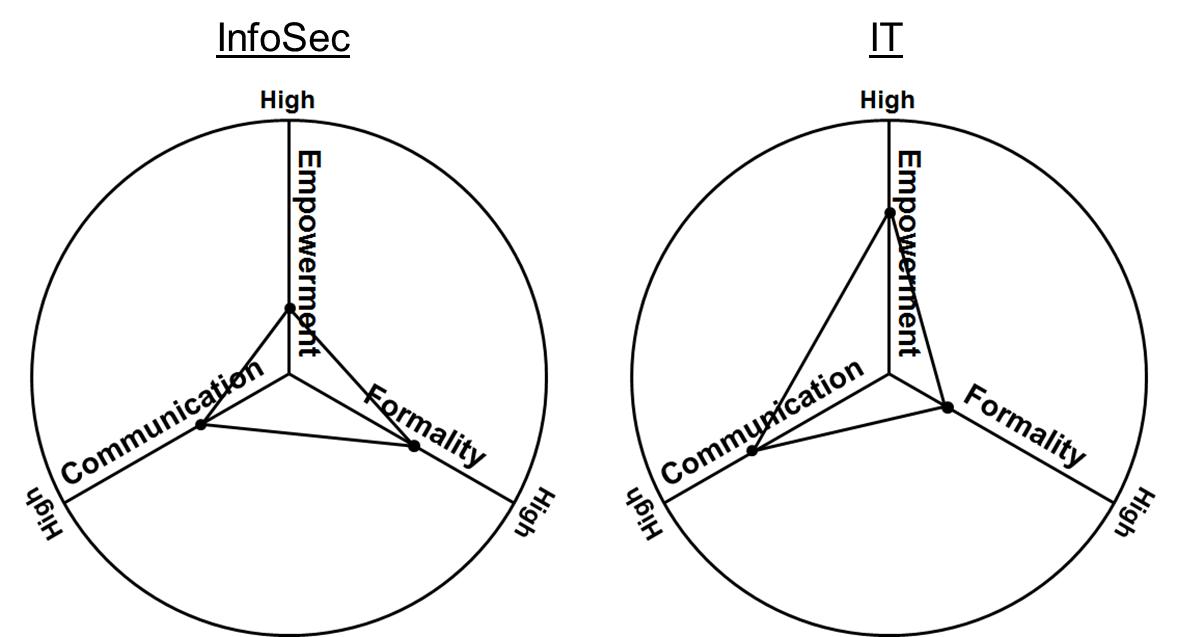

Three important dimensions of organizational style are empowerment, formality, and communication.

Empowerment means how much freedom of action employees have in accomplishing what they’re supposed to accomplish. A key diagnostic is whether managers typically delegate goals or tasks … whether all that matters is the result, or managers involve themselves in how employees are to achieve their results.

Formality is what you think it means: Is everyone relaxed, calling everyone else at all levels by their first name? Or is there a lot of “mister”-ing and “Ms.”-ing going on? Does communication have to follow the chain of command, or does everyone talk with whoever they need to talk with, whenever they need to talk with them?

Is the dress code “Dress for your day,” or is it a twenty-seven-page document that tries to detail exactly what’s allowed in every possible circumstance, but mostly it means wear a business suit?

Communication is about listening, informing, persuading, and facilitating communication among others. In organizations with high levels of communication the key question is, who would benefit by knowing about this? In organizations with low levels the key question is, on a need-to-know basis, who absolutely needs to know about this?

In organizations with high levels of communication, the expectation is that the more people know the better … not just about such matters as the specifications of a piece of work they’re supposed to produce, but also about contextual matters such as what the work is for, what it’s going to directly connect to, and the larger context into which the work is going to fit.

The more everyone knows, that is, the more likely the work they produce will deliver maximum value. Very likely, “everyone” will include more than just employees, too, because very often employees find themselves working with contractors, consultants, suppliers, business partners, and customers.

That contrasts with low-communication organizations. In these, the expectation is that unnecessary communication is a distraction, and worse, it expands the likelihood that sensitive information might leak out of the business and fall into the wrong hands.

Again: While each of us has preferences in these three dimensions, none are better or worse in absolute terms. What matters is understanding that if you work on, say, an Agile-oriented IT applications team, with low levels of formality and high levels of empowerment and communication, and the time comes to bring in Information Security … a team that by its nature tends to be more formal, less empowered, and more limited in its levels of communication (see the figure) … you’d better expend some effort getting your team and the InfoSec team to understand how each other think about life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

What matters isn’t whether you use this particular framework, although I hope you find it helpful. It doesn’t matter whether you graph the result or use some other method to visualize it.

What matters is taking the time to understand how “they” view the world.

And not just how, but why.