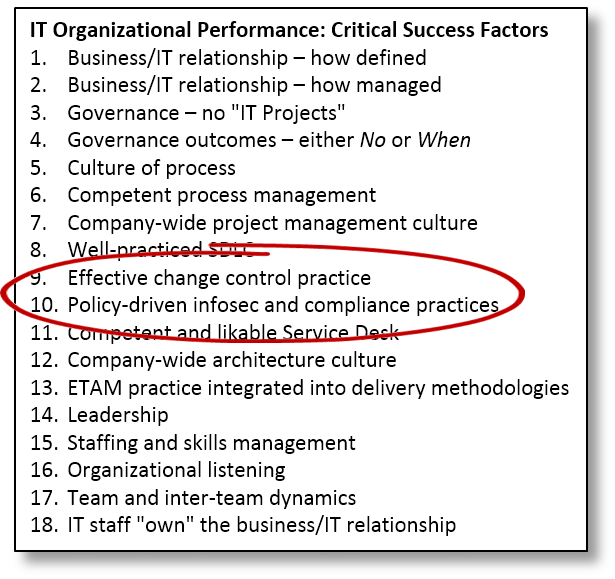

My list of 18 IT critical success factors (CSFs) … the one we’ve been slogging through for the past few weeks and will continue to slog through for the next several weeks … is a terrible list.

It’s terrible because it violates the sacred law of seven plus or minus two.

It’s too long, that is. In principle I should either winnow it down or aggregate some of the factors into broader ones.

I didn’t aggregate because the aggregations would have also included other factors that didn’t make the top 18. I didn’t winnow it down more because I couldn’t — I’m pretty sure that if an IT organization doesn’t get all 18 right, it’s going to find itself in trouble, and it’s going to find itself there sooner rather than later.

My 18 CSFs aren’t exciting or “strategic.” They often range from irritating to downright boring. That makes them no less important. Take this week’s pair: change control and policy-driven information security and compliance.

They’re zzz-inducing, and that’s a good thing because boring is what you want. The alternative is the sort of excitement IT professionals would generally rather avoid.

Change control

ITIL calls this “change management.” I prefer “change control” because it’s less likely to be confused with “business change management,” an entirely different discipline.

Yes, they’re analogous, but analogy isn’t identity. Business change management covers what a company can do to minimize the social disruption that’s likely to occur from changes in how it conducts business. Change control is what IT can do to minimize the chance that a change in technology might disrupt IT operations.

It’s boring. It’s bureaucratic. It’s a set of flaming hoops developers have to jump through to put their new releases into production.

Change control is the discipline that helps IT operations score high in its key metric: the Invisibility Index.

If that isn’t the key metric for your IT operations group, stop reading right now and make it the key metric, because it is the key metric whether you measure it or not.

IT operations is one of those areas that only gets noticed when something goes wrong. Its highest aspiration is for that to never happen.

Every change is a threat to systems stability, which is why controlling those changes is so very important.

Policy-driven information security and other areas of compliance

This is actually a grammatical redundancy, but don’t worry about it. It’s like this: Information security is either driven by a business policy that establishes the company’s risk profile, or else your InfoSec function will have little choice but to do everything possible to prevent anyone from getting anything done.

The same is true of every other compliance topic you have to deal with. The only difference: With the exception of information security, most compliance areas start with formal policies as a matter of habit. With information security, in contrast, having a business policy to start with seems to be the exception.

If you’re in the healthcare industry, you have HIPAA. It’s a formal policy, mandated by the federal government. The policy guides what everyone has to do, inside and outside IT.

If you’re a retailer, the credit card companies have established PCI. It’s a policy designed to protect credit-card data from identity thieves. The policy guides what everyone has to do, inside and outside IT.

There’s no equivalent official, mandated approach to information security to guide what everyone has to do, inside IT and elsewhere besides. And so, companies have two choices. They can either write their own policy (a very good idea), or they can penalize InfoSec whenever there’s any form of intrusion.

That’s a very bad idea, because if InfoSec is going to be punished whenever there’s an intrusion, it will:

- Establish thirty-seven concentric internal firewall perimeters.

- Assign separate passwords for each application everyone uses, each of which will consist of a minimum of 33 randomly-generated characters.

- Lock down every desktop and laptop computer so they can’t do anything at all beyond running a VDI client.

- Disable every USB port on every PC and laptop so no one can move data from one PC to another.

- Disable the email system’s ability to attach files to messages.

Got the picture? InfoSec will have no alternative. With no written policy that establishes the company’s preferred risk posture, all InfoSec will have is the unwritten one: “Any intrusion or data loss is unacceptable.”

And as any time two people exchange information there’s a risk, all communication, right down to hallway conversations, must be forbidden.

It’s our policy.