Last week’s KJR introduced 20 ways of thinking something through, beginning with Outline Thinking and wrapping up with the satisfying but unilluminating Ridicule.

Honesty requires this disclaimer: While I’m quite sure none of these are original, I’m even more sure I didn’t plagiarize someone else’s list. The only credit I can claim is that of the numismatist: I don’t know who stamped these coins, and the only credit I can claim is that I’ve collected them.

Some of you asked for a deeper look at the 20 ways. And while I might stop at 19 – I doubt the world needs techniques for creating better ridicule – I figure starting with Outline Thinking – the first item on the list and arguably the most useful of the bunch – is a safe, if dull bet.

Outlining is top-down decomposition. It’s tempting to stop there, making this the shortest KJR ever posted. But that would be wrong.

Outlining is the tool of choice for documenting your understanding of a subject – of the details and how they fit together.

A successful outline begins with a good subject. It then breaks that subject down to between three and maybe nine topics that are of the same type, and which, taken together, fully encompass the top-level subject as viewed from that perspective.

For example, the subject of your outline might be a project you need to organize. You’ll have to address a number of different topics. For example you’ll have to think through the project team’s composition … that is, the roles you’ll need on the team to do the project’s work. Then there are the work products its team will have to produce to accomplish the project’s objective and goals.

And, not to be ignored, you really ought to figure out the tasks the team will have to execute to create those work products.

To figure out what these tasks are, the project manager will need to outline them. The project management buzzword is “work breakdown structure,” but don’t let that throw you – it’s an outline. So far so good.

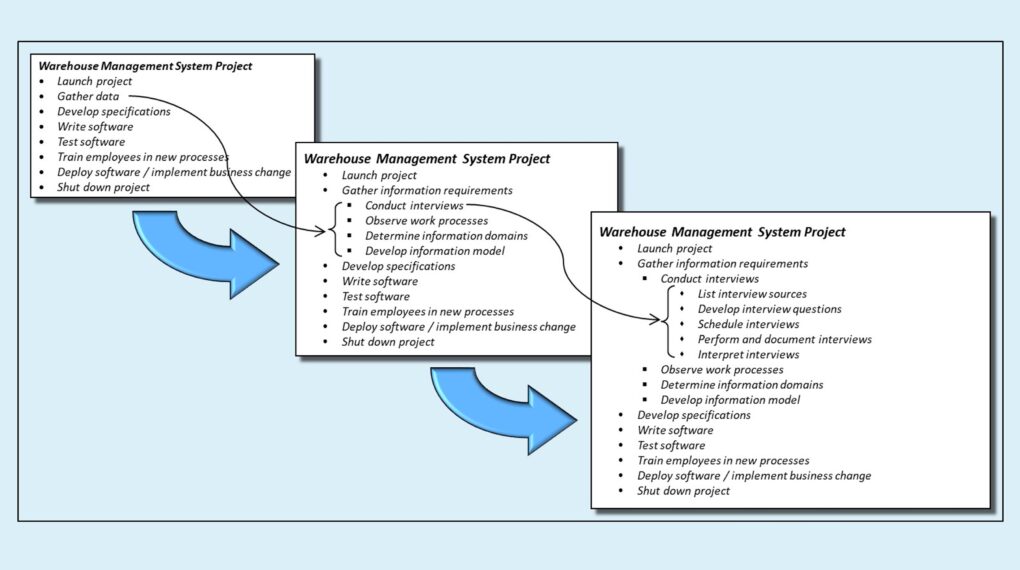

You start the process of organizing project tasks by answering the question, “What are the tasks that make up the project?” That results in a top-level view of the project task outline, as shown in the box at the top left in the figure below, taken from the demonstration project used in Bare Bones Project Management – implementing a warehouse management system.

Next, you ask the equivalent question about each project task that you asked about the project: “What are the sub-tasks that make up this task?” The figure’s middle box shows the result for the “Gather data” task, re-casting Gather data to Gather information requirements to help clarify what will be needed. In a real project you would ask the same question about every other top-level task, too.

The figure’s lower-right-hand box shows the result of taking the Conduct interviews sub-task to one more level.

Then you would continue until you run out of sub-sub-sub etcetera tasks. Or, if you’re smart (and lazy, but that’s just saying the same thing twice) you’d delegate the rest of the outlining to the experts on your project team best-suited to do so.

Bob’s last word: As you can see, outlining is an excellent tool for thinking a subject through to understand it better, whether the subject is project tasks, the components needed to assemble a piece of Ikea furniture (pro tip: yes, an Allen wrench is a necessary component, but no, it isn’t a sufficient one), or a meal.

What makes it such a useful tool is that it lets you understand the subject you’re figuring out at whatever level of depth you need, without having to keep all that depth in your head all at once.

Outlining, that is, is a terrific way to keep your head from exploding.

Bob’s sales pitch: Speaking of thinking, The Cognitive Enterprise, which I co-authored with my colleague Scott Lee, is, so far as I can tell, the only business book with “cognitive” in the title that isn’t about applying artificial intelligence to business situations. It asks what we think is a more profound question: What would an enterprise that acts purposefully look like – one that has more in common with predators than with ecosystems – and how would you build one.