Leaders encourage. Managers direct. Leaders foster. Managers enforce.

With the best leadership, employees don’t realize they’re following — they’re going where they want to go. The management alternative? Employees don’t think they have a choice in the matter.

Am I being fair? Not entirely. Leaders and managers are the same people. Management gets work out the door. Leadership gets people to follow. So in the context of business, leadership is a tool that lets managers get the same or better results without having to work so hard.

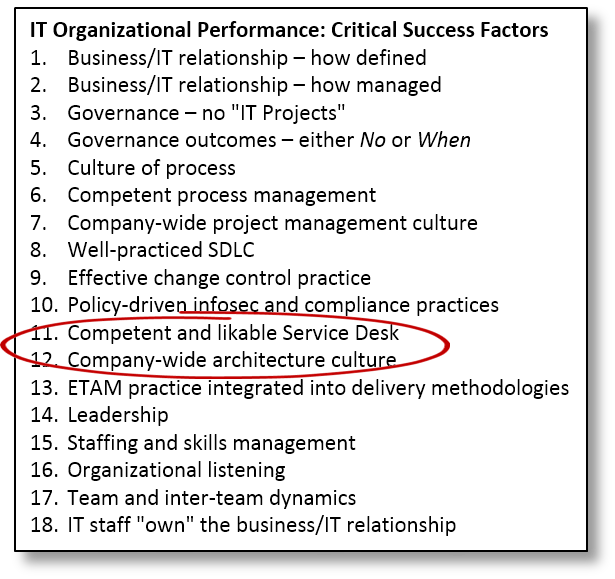

Which brings us to our next two IT critical success factors … two factors that at first blush might not seem to have much in common. They are a competent and likable service desk; and a culture of architecture, not only in IT but throughout the business.

What they have in common: They’re both about getting people to go where IT wants them to go with no sense of coercion.

Service desk

The service desk is also known as the help desk, except where it’s known as the helpless desk.

The service desk is the most important part of the IT organization. If this point isn’t clear, re-read the article that launched this series: “In IT, relationships come first,” (KJR, 3/25/2013).

Or just re-read the title.

Relationships come first, because if IT’s relationship with the business is broken, it can’t succeed at anything. The people we depend on throughout the rest of the business will see to that. Distrust has that effect.

The relationship between IT and the rest of the business improves or deteriorates every time one employee in IT interacts with one employee outside IT. Enter the service desk. Its staff interactions with employees throughout the business more than any other part of IT, which means it has more impact on the relationship between IT and the rest of the business than any other part of IT.

If service desk staff aren’t competent, IT looks incompetent every time they try to fix a problem. Take it another step: If the service desk staff aren’t likeable, this will reflect on the impression business employees have of IT. Not just the service desk. All of IT.

One more thing: Employees contact the service desk when they need help … which is why “help desk” is probably the better name. And in case this has escaped anyone’s attention, they’re contacting the help desk because something has gone wrong with the information technology they use to get their jobs done.

Which means they’re generally a bit tense, and like most people who are tense because something has gone wrong, their inclination is to find someone to blame. Like, for example, IT, which put the ferschlugginer technology that’s misbehaving on their desk in the first place.

Which in turn leads to the single most common piece of advice I’ve given my CIO clients since I first started consulting: If the business/IT relationship is broken, fix the service desk first.

Architecture culture

When IT has finished singing, dancing, and playing the tuba, the outcome of enterprise technical architecture management is a collection of technology standards.

The point is to make sure the technical architecture facilitates whatever technology changes the company decides its needs instead of raising barriers, but the point is different from how IT gets to the point.

It gets to the point through the creation of standards, after which it really has just two ways to get everyone to comply with them: It can either create the architecture police, achieving compliance through enforcement, or it can foster a “culture of architecture,” at which point good architecture is “how we do things around here.”

Architectural standards have an intriguing property: They’re good for the business without being good for anyone in the business. The reason? Maintaining a strong architecture means today’s business sponsors have to spend more so that future business sponsors can spend less. So architecture is a hard sell.

Add to that one additional property: The nature of good architecture, and how it leads to lower costs in the future, is hard to explain convincingly in business terms, because it’s all about engineering, not cash flows.

Which is why successful ventures into technical architecture management require a culture of architecture that extends beyond IT, into the rest of the business.

Along with one more thing: A good relationship. Because for architecture to happen, they need to trust us, too.