“Haven’t you read Amazon’s and Microsoft’s recent press releases on this?”

This was in response to a challenge to the “save money” argument for migrating applications to the public cloud.

I understand just as well as the next feller that press releases serve a valid purpose (what’s the feminine of “feller” anyway?). When a company has something important to announce, press releases are the more than 140 characters explanation of what’s going on.

That’s in contrast to the difference between facts (“We’re changing our pricing model”) and smoke (“You’ll save big money”). I say smoke because:

First and foremost, Fortune 500-size corporations that can’t negotiate pricing for servers and storage comparable to what Amazon and Microsoft pay for the gear they use to run AWS and Azure just aren’t trying very hard. They have access to the same technology management tools, practices, and talent, too.

Second: Smart companies are building their new applications using cloud-native architectures — SOA and microservices orientation; multitenancy; DevOps-friendly tool chains that automate everything other than actual coding, and so forth (“and so forth” being ManagementSpeak for “I’m pretty sure there’s more to know, but I don’t know it myself”).

But migrating to cloud-native architectures that are easily shifted to public or hybrid clouds is quite different from migrating applications designed for data-center deployment. And it’s the latter that are the ones that are supposed to save all the money.

Sure, applications coded from non-SOA, non-microservices, non-multi-tenant designs can probably be recompiled in an IaaS environment. But once they’ve been recompiled they’ll probably need significant investments in performance engineering to get them to a point where they aren’t unacceptably sluggish.

Oh, one more thing: Moving an application to the cloud means stretching whatever technologies are used for application and data integration through the firewall and public network that now separates public-cloud-hosted applications to those that have yet to be migrated.

Based on my admittedly high-level-only understanding, not even all enterprise service buses can achieve high levels of performance when, instead of moving transactions around at wire or backplane speeds, they’re now limited to public networking bandwidths and latencies.

Complicating integration performance even more is the need to integrate applications hosted in multiple, geographically disbursed data centers, as would be the case when, for example, a company migrates to, say, Salesforce for CRM, internal development to Azure, and financials and other ERP applications to Oracle Cloud.

For many IT organizations, integration is enterprise architecture’s orphan stepchild. Lots of companies have yet to replace their bespoke interface tangle with any engineered interface architecture.

So lifting and shifting isn’t as simple as lifting and then shifting, any more than moving a house is as simple as jacking it up, putting it on a truck, and hauling it to the new address. Although integration might not be as fraught as the house now lying at the bottom of Lake Superior.

Which isn’t to say there’s no legitimate reason to migrate to the cloud. (Non-double-negative version: There are circumstances for which migrating applications to the cloud makes a great deal of sense.) Here are three circumstances I’m personally confident of, and I’d be delighted to hear of more:

> Startups and small entrepreneurships that lack the negotiating power to drive deep technology discounts, and that will benefit from needing a much smaller full-time and permanent IT workforce.

> Applications that have wide swings in workload, whether because of seasonal peaks, event-driven spikes, or other drivers, the result is a need to rapidly add and shed capacity.

> A Mobile workforce or user base that needs access to the application in question from a large number of uncontrolled locations.

At least, this was the situation the last time I took a serious look at it.

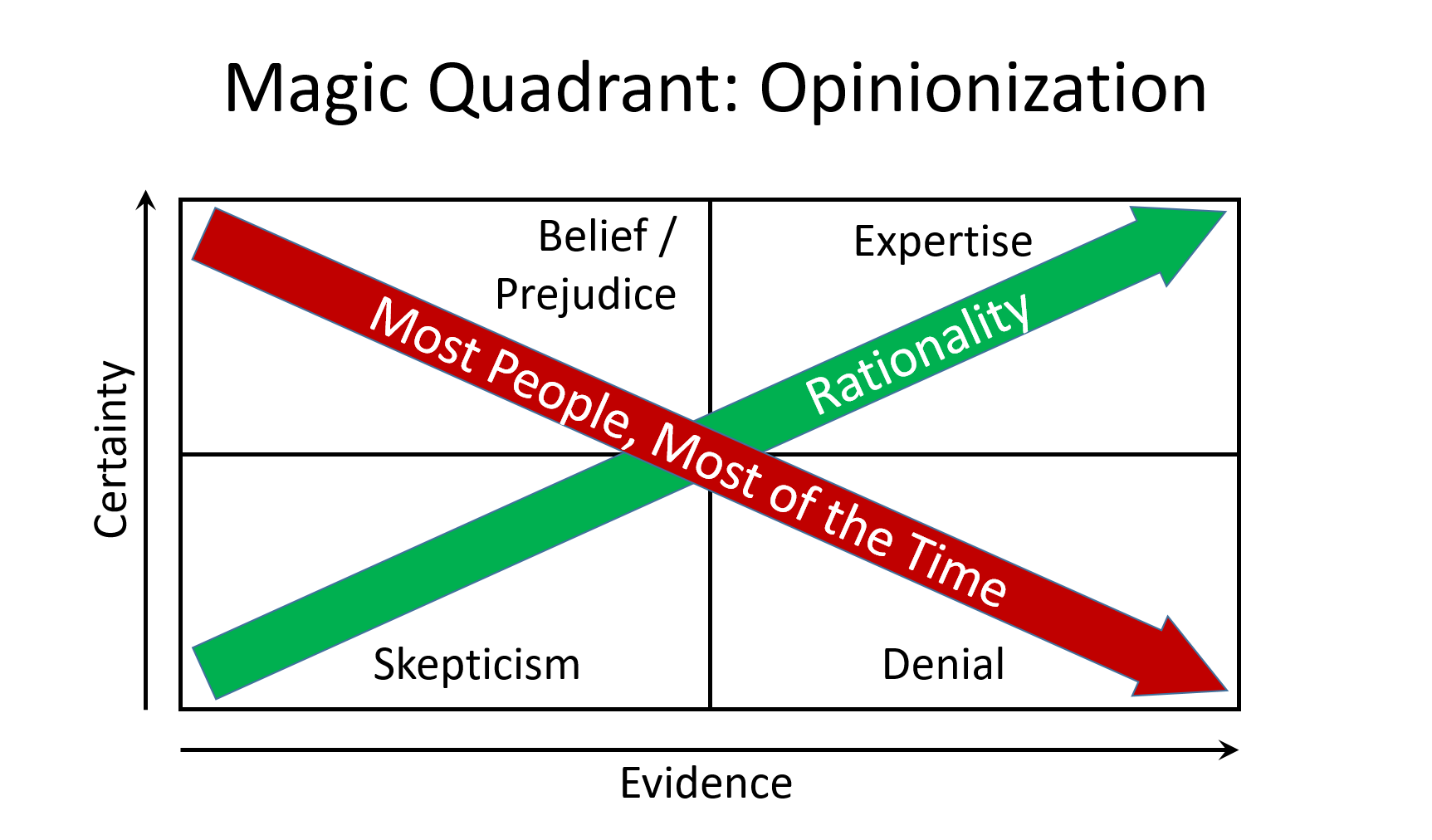

But this isn’t a column about the cloud. It’s about the same subject as last week’s KJR: How to avoid making decisions based on belief, prejudice, and denial. The opening anecdote shows how easy it is to succumb to confirmation bias: If you want to believe, even vendor press releases count as evidence.

In that vein, here’s a question to ponder: Why is it that, after centuries of success for the scientific method, most people most of the time (including many scientists) operate so often from positions of high certainty and low evidence?

The answer is, I think, that uncertainty causes anxiety. And people don’t like feeling anxious.

But collecting and evaluating evidence is hard and often tedious work — not a particularly popular formula.

Isaac Asimov once started a Q&A session by saying, “I can answer any question, so long as you’ll accept ‘I don’t know’ as an answer.”

If Dr. Asimov was comfortable not knowing stuff, the rest of us should be at least as comfortable.

I think.