ManagementSpeak: When hiring, the first question I ask is “Can I trust this person?”

Translation: When hiring, the first question I ask is, “Does this person remind me of me?”

Even though he chose to remain anonymous, I’m sure we can trust this week’s contributor.

Year: 2008

Rights, privileges, fairness and equality

Way back when, before the World Wide Web, the Internet was a small, close community. It was self-policing; as much as any other technique the small-town punishment of disapproving looks took care of most problems.

As the Internet grew, and as more and more money entered the picture, self-policing stopped being effective. Formal controls became important.

Before then, when the population of the American West was small, cattlemen grazed their cattle wherever they found good forage … as did sheep ranchers. As the population grew, so did the need for fences. And sheriffs.

When populations are small and “six degrees of separation” is usually six, and always five degrees more than anyone needs to meet anyone else, formal regulations and controls serve no useful purpose.

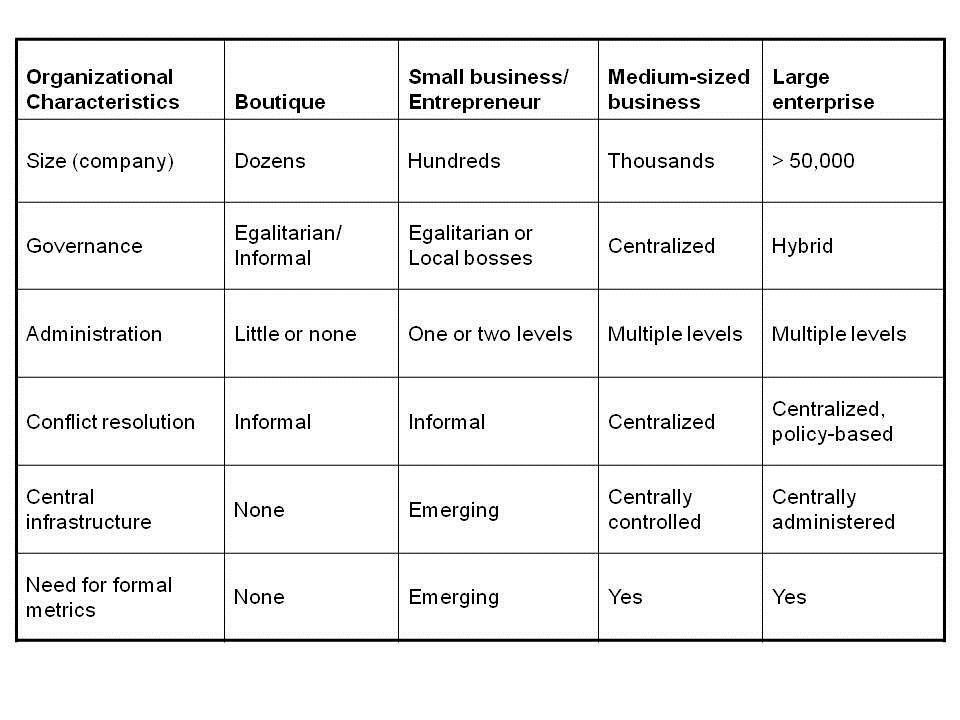

In Guns, Germs and Steel (1997), Jared Diamond analyzed the correlation between the size of a society and its governance. Translated into corporate terms, and with some allowances for the differences between societies and businesses, it comes out more or less as the table shows: As companies grow from boutique to large enterprises, governance, administration and conflict resolution all become more formal and less flexible. This need for more formality — for shifting from relationship-driven decision-making to rule-driven decision-making — happens because of how hard it is to establish mutual trust between strangers.

In response to the series of columns I wrote earlier this year on this subject, and in particular on PC lockdown and related policies, my friend and client Dave Kaiser raised this question:

You give freedom to your best team members who are taking the Blackberries around and doing what is needed to get the job done. Clock punching Jim has never worked an extra minute in his entire life. He starts complaining because he isn’t granted the same rights. You explain it to Jim and he gives you the argument that this isn’t fair — that you have to treat everyone the same.

Well, no you don’t. Or else, yes you do, if that’s your corporation’s style, which, as companies grow, becomes increasingly likely. Resist the trend. Treating people fairly isn’t the same as treating them the same.

Other than high-risk situations, giving employees the benefit of the doubt is a good idea. If a Blackberry should be useful and an effectiveness enhancer, enhance away.

Giving the benefit of the doubt isn’t the same as ignoring a large pile of evidence. If you’ve worked with Clock-Punching Jim long enough to know he considers a Blackberry to be an entitlement that accompanies employment, and can predict its primary value will be to let Jim ostentatiously ignore team discussions in order to click away … don’t give him one.

When he complains you aren’t being fair, reply that of course you’re being fair. You issue Blackberries to every employee who has demonstrated through performance that it’s a good business investment. He, on the other hand, has demonstrated an uncanny ability to work at exactly the level you define as Just Barely Good Enough. In your judgment, a Blackberry for him would not be a prudent business investment.

That’s the harsh approach, and while, over a barley pop or two, I pretend to enjoy this way of dealing with substandard employees, in fact I don’t recommend it, nor do I practice it myself.

There are reasons people are the way they are. For the most part, their attitudes and behaviors are shaped by the expectations they’ve developed based on their life experiences. If Jim is a clock puncher, there’s a reason for it. This doesn’t mean you can always overcome such things. It does mean sarcasm when discussing employee performance is like cake frosting — tasty and satisfying for a moment or two, but not nutritious and helpful in the long run.

So conduct the more productive version of the conversation instead. You issue Blackberries to every employee who has demonstrated by way of performance that it’s a good business investment. Those are also the employees who receive the larger raises, bonuses, and promotions, and for the exact same reasons.

Then express your confidence in his abilities, explain your concerns about his apparent lack of motivation, and let him know that what happens next is up to him. If he decides to work to his potential you’ll help him take his career as far as it can go. If he has no interest in doing more than he has to, he’ll keep his job, but you won’t invest a lot of time and energy in him.

Or a Blackberry.