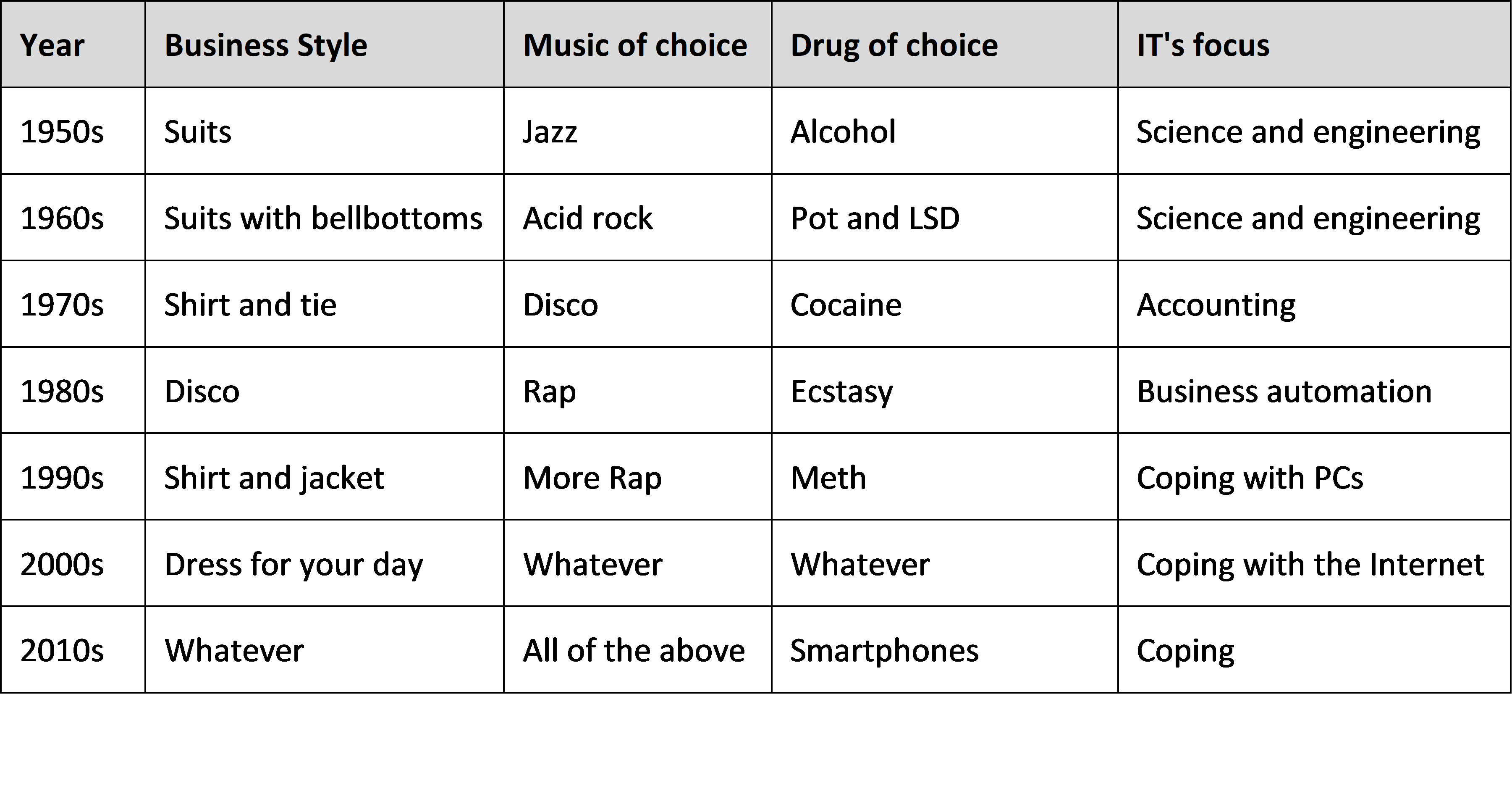

A quick history of the United States:

If you’re running an IT organization, you’re probably coping and having a hard time doing it. IT has evolved from supporting core accounting, to all business functions, to PC-using autonomous end-users; to external, paying customers on the company’s website; to mobile apps, the company’s social media presence, its data warehouse, big-data storage and analytics … all while combatting an increasingly sophisticated and well-funded community of cyber attackers.

What hasn’t evolved is IT’s operating model — a description of the IT organization’s various moving parts and how they’re supposed to come together so the company gets the information technology it needs.

Your average, everyday CIO is trying to keep everything together applying disco-era “best practices” to the age of All of the Above.

Defining a complete IT All-of-the-Above operating model is beyond this week’s ambitions. Let’s start with something easier — just the piece that deals with the ever-accelerating flow of new technologies IT really ought to know about before any of its business collaborators within the enterprise take notice.

We’ve seen this movie before. PCs hit the enterprise and IT had no idea what to do about them. So it ignored them, which was probably best, as PCs unleashed a torrent of creativity throughout the world of business (assuming, of course, that torrents can be put on leashes in the first place). Had IT insisted on applying its disco-age governance practices, to PCs, all manner of newly automated business processes and practices would most probably still be managed using pencils and ledger sheets today.

Eventually, when PCs were sufficiently ubiquitous, IT got control of them, incorporating them into the enterprise technical architecture and developing the various administrative and security practices needed to keep the company’s various compliance enforcers happy, to the extent compliance enforcers are ever happy.

Then the World Wide Web made the Internet accessible to your average everyday corporate citizen, and IT had no idea what to do about it, either. So it did its best to ignore the web, resulting in another creativity torrent that had also presumably been subjected to IT’s leash laws.

It was a near point-for-point replay.

Now … make a list of every Digital and Gartner Hype Cycle technology you can think of, and ask yourself how IT has changed its operating model to prevent more ignore-and-coopt replays.

This is, it’s important to note, quite a different question from the ones that usually blindside CIOs: “What’s your x strategy?” where x is a specific currently hyped technology.

This is how most businesses and IT shops handle such things. But as COUNT(x) steadily increases, it’s understandable that your average CIO will acquire an increasingly bewildered visage, culminating in the entirely understandable decision to move the family to Vermont to grow cannabis in bulk while embracing a more bucolic lifestyle.

The view from here: Take a step back and solve the problem once instead of over and over. Establish a New Technologies Office. Its responsibilities:

- Maintain a shortlist of promising new technologies — not promising in general, promising for your specific business.

- Perform impact analyses for each shortlist technology and keep them current, taking into account your industry, marketplace and position in it, brand and customer communication strategy, products and product strategies, and so on. Include a forecast of when each technology will be ripe for use.

- For each technology expected to be ripe within a year, develop an incubation and integration plan that includes first-business-use candidates and business cases, the logical IT (or, at times, non-IT) organizational home, and a TOWS impact analysis (threats, opportunities, weaknesses, strengths). Submit it to the project governance process.

Who should staff your new New Technologies Office? Make it for internal candidates only, and ask one question in your interviews: “What industry publications do you read on a regular basis?”

Qualified candidates will have an answer. Sadly, they’ll be in the minority. Most candidates don’t read.

They’re part of the problem you’re trying to solve.