Go figure.

The success rate for mergers and acquisitions is now below 20%. And yet, they’re more popular than ever.

Why might that be? Speaking, as a spectator and occasional supporting consultant, it’s because, superficially, they appear to be a way for companies to:

- Buy customers instead of having to win them.

- Add new, complementary products without having to undertake the risky business of developing them.

- Gain access to new regions with different rules of engagement without having to build the abilities needed to do business there.

- Fool unwary investors by posting year-over-year revenue gains without having actually increased revenue.

Superficially, that is, acquisitions look like a lower-risk alternative to organic growth.

And so, in spite of overwhelming evidence that this has nothing to do with How Things Work Here on Earth, mergers and acquisitions continue to be one of the most popular business growth strategies.

This is a big, complex topic, surrounded by plenty of AFG. Over the next few weeks we’ll talk about some of the practicalities of achieving M&A success … or at least, avoiding M&A failure … that don’t get a lot of attention from the standard sources of business wisdom.

Starting with this one, which should be tattooed on the foreheads of everyone involved: Above all, do no harm.

Or, if you prefer Aesop to Hippocrates, Don’t Kill the Golden Goose!

Take, for example, this common mistake:

An enterprise-scale company acquires a small entrepreneurship to add its products to the enterprise portfolio.

The small and profitable entrepreneurship succeeds, it turns out, in part by running lean, doing without much of the bulletproofing needed by large enterprises but not entrepreneurships.

But in the pursuit of fairness, the enterprise loads up the entrepreneurship — now a separate business unit — with all that bulletproofing and the general and administrative overhead charges that go with it.

Superficially (there’s that word again) this is reasonable: Instead of running its own email system, for example, the newly acquired business unit gets to use the enterprise unified communication system.

Except that the entrepreneurship didn’t run a unified communication system. It used Slack, which might or might not scale to enterprise proportions but which is dirt cheap and was very good at supporting the collaboration that made the entrepreneurship work.

The result: Disruption during the transition, and less-effective collaboration paid for by higher overhead costs once the transition is done.

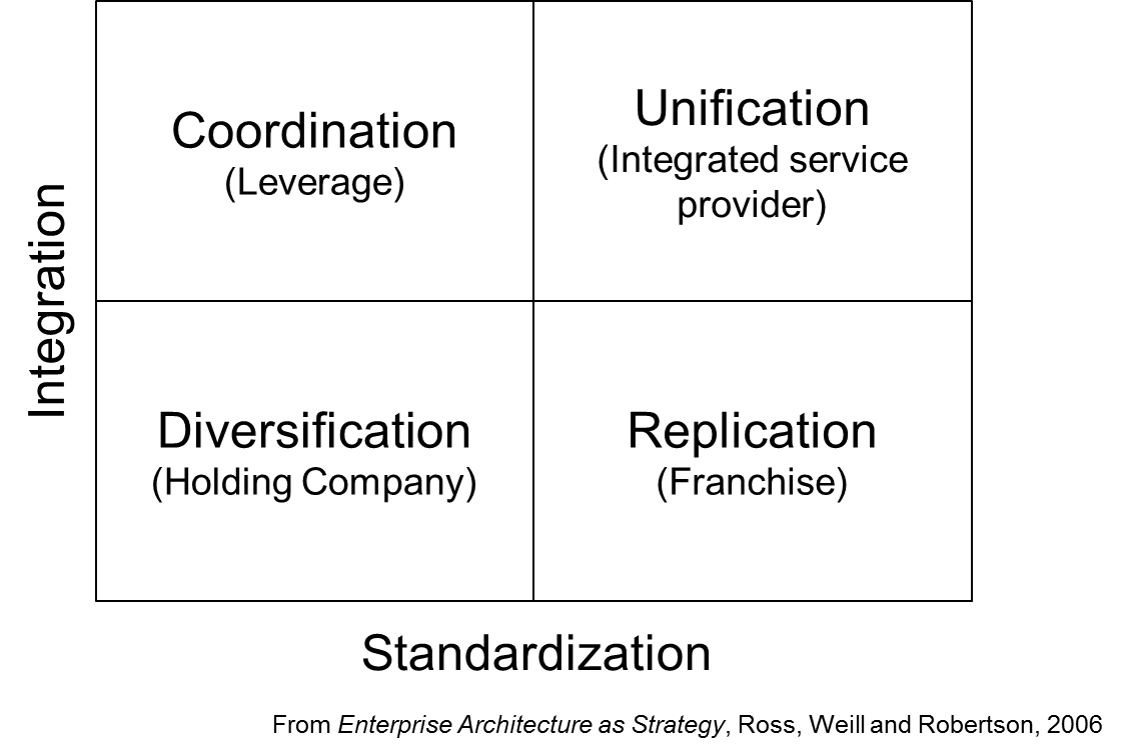

Acquiring companies make this sort of mistake all the time, usually by failing to think through the most basic element of enterprise business architecture — the desired level of unification.

As shown in the diagram, when an enterprise acquires a business it has three types of decision to attend to: What to standardize, what to integrate, and what to leave alone.

A company standardizes when all business units have to use the same (as examples) core accounting software, chart of accounts, and office supplies provider. Standardization usually results in nicer discounts for the standardized items. Theoretically it should reduce support costs as well — an Integration benefit that’s a frequent source of intense disappointment.

Unlike standardization, where everyone gets their own copy of the standardized item, with integration everyone shares the same copy. “Copy,” by the way includes such things as shared IT support staff, which is why expectations of lower support costs so often end up unfulfilled.

Here’s why. Imagine the entire enterprise standardizes on the Microsoft suite of productivity and collaboration tools — MS Office, Exchange, Outlook, SharePoint, and Skype for Business. In theory this means IT support staff only need to learn how to support this one collection of products instead of needing, say, Slack expertise as well.

The disappointment arrives when it turns out staffing ratios depend on the number of people needing support, not the number of products needing support. If IT needs 50 support staff if it’s standardized on the Microsoft product line, needing 45 to support the Microsoft products and 5 to support something else is no more expensive.

Back to the big picture: Whether you should standardize an acquisition, integrate it, some of each, and to what extent all depend on how the enterprise plans to operate them in the future. If it wants to own and run the same successful business it just bought, the best solution is to mostly leave it alone — to run as a holding company so as not to kill the golden goose.

But it’s all contextual: If an enterprise buys a failing business with promising products or access to promising markets, it should arrive at a completely different business architecture.

* * *

In case you have a suspicious nature and think I’m writing about Dell’s coming acquisition of EMC, or NTT DATA’s coming acquisition of Dell Services, nothing could be further from the truth.

Among the reasons: I have no involvement in the former and as far as the latter is concerned I’m just a passenger on that train — I don’t know anything more about either transaction than you do.