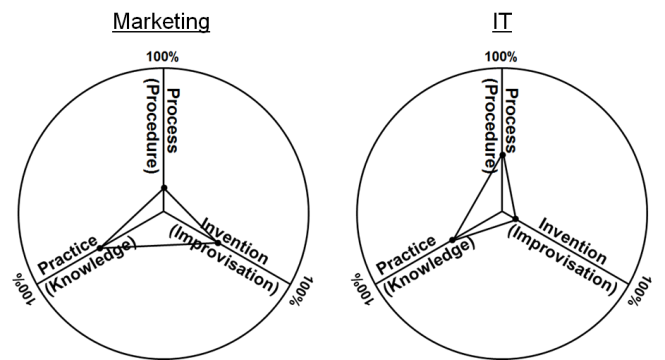

Process is a blurry word.

It should be limited to situations where employees follow a sequence of well-defined steps that deliver repeatable, predictable results. Mass production, that is.

Instead, it’s often defined as “how work gets done,” however it gets done. Which leads to sloppy thinking, along the lines of, “Hmmm. Application development is a process. We’re having trouble with it. The problem must be that we haven’t defined the steps well enough.”

That way lies madness. When the time comes for developers to figure out how to put a module, object, component or service together, there’s a certain amount of figuring things out that can’t be reduced to a recipe.

In other words, application development is a practice, not a process. You don’t want repeatable, predictable results, because your developers only create each module once.

If IT was Nissan, app dev would correspond to the design department. It only created one production-ready blueprint of the 2013 Altima. It’s manufacturing that produces thousands of identical Altimas based on design’s blueprint.

None of which means process doesn’t matter in IT. IT does lots of things over and over again, from provisioning virtual servers, to deploying new desktops and laptops, to administering (and please, I beg you — not “administrating”!) access rights, privileges and restrictions for newly hired employees.

And even many practices, like troubleshooting, are embedded into broader processes like incident management, which is to say you can’t diagnose and fix all problems just by following a recipe (although “reboot” does solve a distressingly large fraction of them.

But before IT gets to the actual troubleshooting, it ought to follow a very well-defined set of steps for:

- Capturing and documenting the problem.

- Attempting to troubleshoot it during the call, assuming the problem was called in (embedded practice).

- Calculating the incident’s priority relative to everything else that’s going on.

- Assigning the ticket to a qualified technician.

- Resolving the issue (another embedded practice).

- Communicating status back to the caller at well-defined points in the process.

- Confirming the solution with the caller.

- Logging the resolution.

For all those situations where, like incident management, consistency ranks high on your list of Things That Matter, making sure staff follow a well-designed and well-documented process is how you get it to happen.

One problem: You can’t. Or, rather, you shouldn’t. Getting everyone to follow a process is a lot like the legendary guy who had a dog with no legs: Every morning he had to take Spot out for a drag.

When you have to drag employees along, it’s a … well, it’s a drag.

One more problem: You can’t. If you’re the CIO or IT Ops manager, it’s up to the Service Desk manager to make sure the incident management process happens the way it’s supposed to.

Now imagine, just for the sake of argument, that what the Service Desk manager knows how to do is supervise the work. That’s a very different matter from managing a process, and it leads to very different, generally worse results.

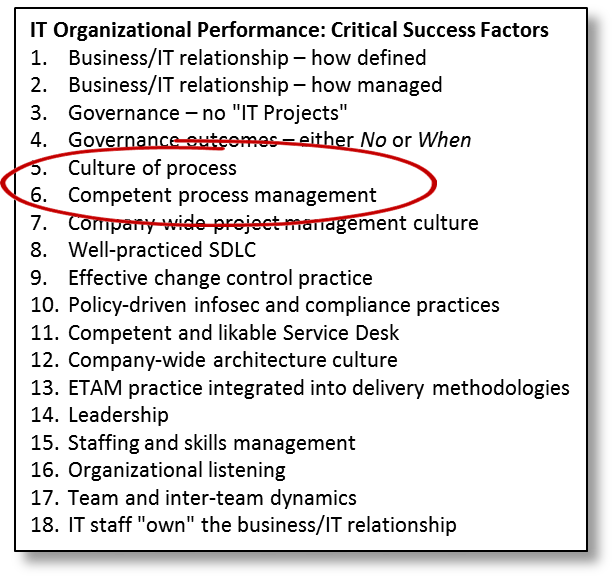

Which leads to this week’s pair of IT critical success factors: For those situations where process matters (roughly half of what IT deals with on a regular basis), what matters most is having (1) a “process culture,” and (2) managers who understand how to manage processes, and who embrace the idea of managing this way.

Process culture

Since founding IT Catalysts, my now-quiesced consulting company, I’ve used the definition of culture taught to me by my now-retired, anthropology-trained business partner: Learned behavior people exhibit in response to their environment.

A simpler version: In business, culture is “how we do things around here.” If you want staff to follow well-defined, well-documented processes, following well-defined, well-documented processes has to be how we do things around here. If it is … if you have a process culture … process will happen more or less automatically. If it isn’t, all you’ll get is malicious obedience.

Process management

Remember the Service Desk manager who likes supervising the work? That’s a problem if what you want is the consistency that comes from following well-defined processes. So it matters that process managers think in terms of establishing metrics and targets, setting up checklists and check-offs, and having regularly scheduled process review and improvement meetings. And, it matters that whenever possible such topics as priority-setting should be handled by algorithms instead of personal preference and judgment.

It matters enough that managerial competence in process management qualifies as another IT CSF.

Because if you think the IT staff can wreck your plans through malicious obedience, just imagine how much damage one of your managers can do.