Back when re-engineering was all the rage, a reported 70% of all re-engineering projects failed.

That’s in contrast to the shocking failure rate I ran across a few years later for CRM implementations, 70% of which failed.

On the other hand, the statistic tossed around for mergers and acquisitions is that 70% don’t work out.

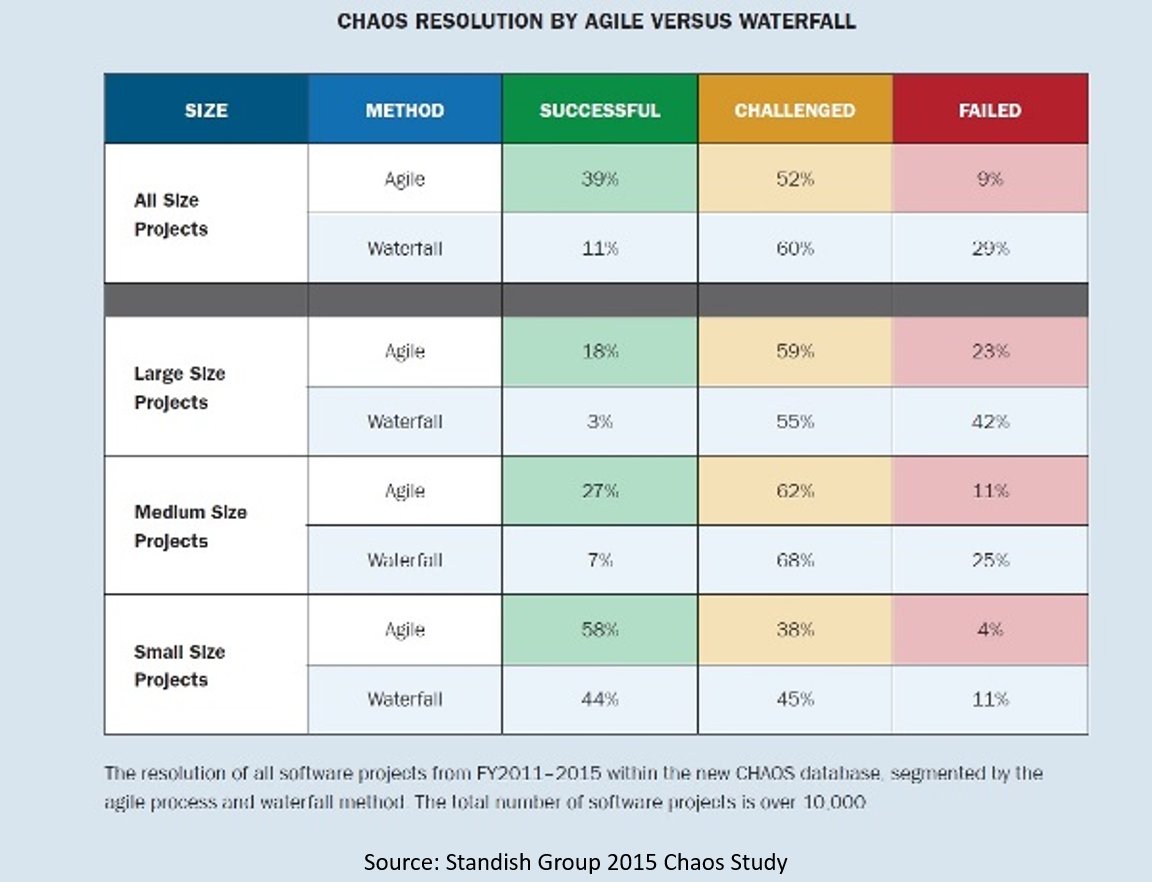

On the other hand, the most recent numbers for large application development projects show that, in round numbers, 70% have results in the disappointing to failed completely range.

At least, that’s the case for large application development projects executed using traditional waterfall methods, depending on how you count the “challenged” category.

And oh, by the way, just to toss in one more related statistic, even the best batters in baseball fail at bat with a failure rate of just about 70%.

What’s most remarkable is how often those who tabulate these outcomes are satisfied with the superficial statistic. 70% of re-engineering projects fail? There must be something wrong with how we’re executing re-engineering projects. 70% of CRM implementations fail? What’s wrong with how we handle these is a completely different subject.

As are the M&A, application development, and baseball at-bat percentages.

But they’re not different subjects. They are, in fact, the exact same subject. Re-engineering, customer relationship management, mergers and acquisitions, and hitting a pitched baseball are all intrinsically hard challenges.

And, except for hitting a baseball, they’re the same hard challenge. They’re all about making significant changes to large organizations.

Three more statistics: (1) Allocate half of all “challenged” projects to “successful” and half to “failed” and it turns out more than 75% of all small Agile application development projects succeed; (2) anecdotally, 100% of all requested software enhancements complete pretty much on schedule and with satisfactory results; and (3) during batting practice, most baseball players hit most of the balls pitched to them.

Okay, enough about baseball (but … Go Cubbies!).

Large-scale organizational change is complex with a lot of moving parts. It relies on the collaboration of large numbers of differently self-interested, independently opinionated, and variably competent human beings. And, like swinging a bat at a pitch, it’s aimed at an unpredictably moving target.

The solution to the high organizational change failure rate is very much like how to not get hurt when driving a car at high speed into a brick wall: Don’t do it.

The view from here: Extend Agile beyond application development, so large scale change becomes a loosely coupled collection of independently managed but generally consistent small changes, all focused on the same overall vision and strategy.

Turns out, I wrote about this quite some time ago — see “Fruitful business change,” (KJR, 5/26/2008) for a summary of what I dubbed the Agile Business Change (ABC) methodology.

I’ll provide more specifics next week.

* * *

Speaking of not providing more specifics, here’s this week’s Delta progress report:

Gil West, Delta’s COO, has been widely quoted as saying, “Monday morning a critical power control module at our Technology Command Center malfunctioned, causing a surge to the transformer and a loss of power. When this happened, critical systems and network equipment didn’t switch over to backups. Other systems did. And now we’re seeing instability in these systems.”

That’s all we have. Two weeks. Three sentences. Near-zero plausibility.

Leading to more information-free speculation, including lots of unenlightened commentary about Delta’s “aging” technology, even though this can’t have had anything to do with it. Delta’s actual hardware isn’t old and decrepit, nor is anyone suggesting the problem was a failed chip in its mainframes. Delta’s software may be old, but if it ran yesterday it will run tomorrow, unless an insufficiently tested software change is put into production today.

Nor does a loss of power cause systems to switch over to backups. It causes the UPS to kick in and keep everything running until the diesel generators fire up. Oh, and by the way, much smaller businesses than Delta are smart enough to have power supplied by two different substations, entering through two different points of presence, feeding through different transformers, so as to not have a single point of failure.

But because nobody is insisting on detailed answers from Delta, it’s doubtful we’ll ever know what really happened.

Which, in the greater scheme of things, probably doesn’t matter all that much, other than leading us to wonder how likely it is to happen again.